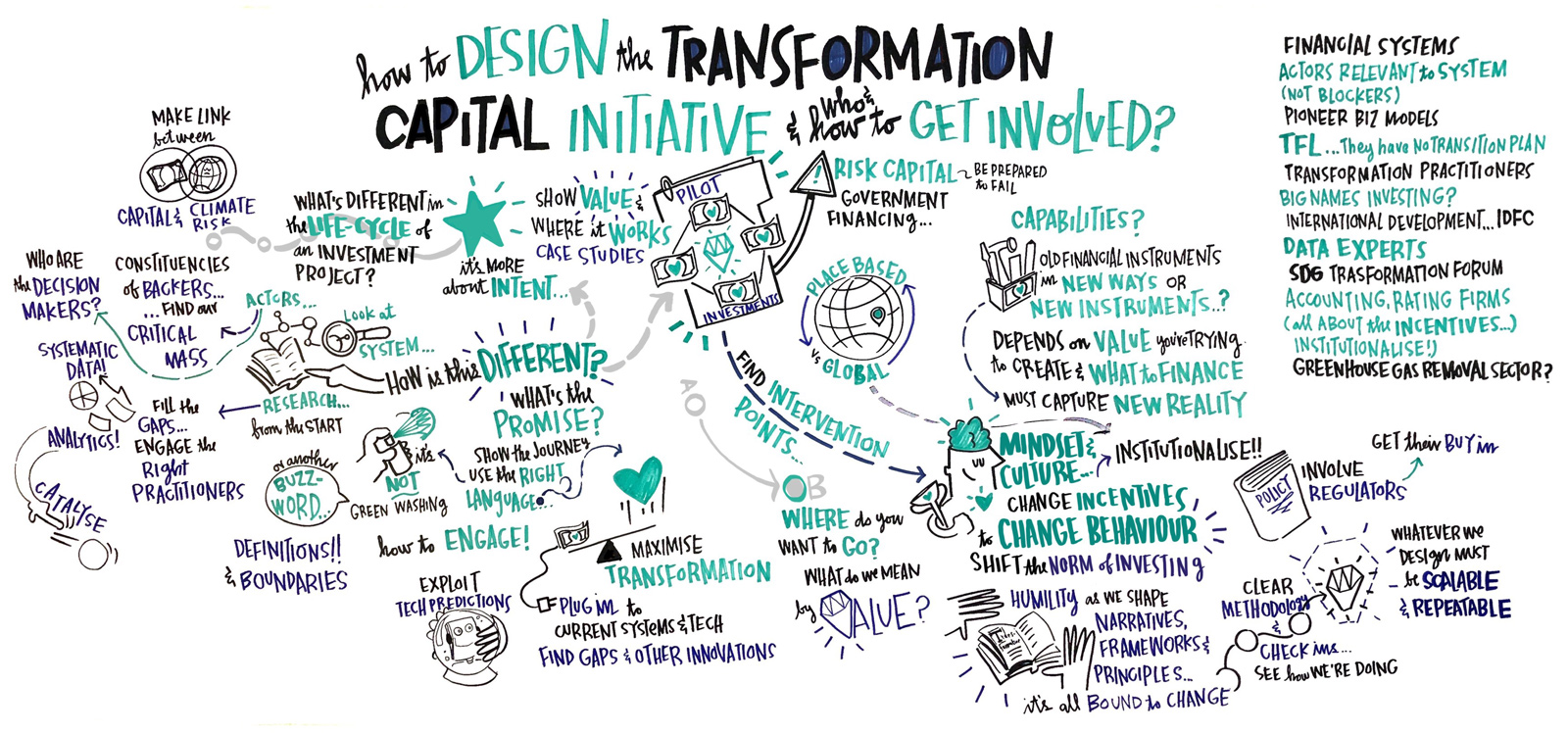

Visual scribing by Fernanda de Uriarte, © TransCap Initiative/EIT Climate-KIC, July 2019

Jay’s parents were entrepreneurs who started a medical wheelchair cushion company during his childhood in Boulder, Colorado. “I grew up with every dinner table conversation about business, and as a family we are now on our third company,” he says.

Researching and teaching about sustainability and innovation in business, Jay “always had in the back of my mind: is there a connection between family enterprise and sustainability?” He was confident that in the world of impact investing (defined as providing funding to a cause or entity with a goal of achieving societal benefit), family business owners were playing a key role.

Sustainability and family businesses—a natural fit

In his research, Jay found that many of the investors in companies with sustainability-focused products were from family businesses. “Private wealth has the most flexibility around their definition of success,” he explains, “whereas investors such as pension funds and 401(k) plans are legally obligated to maximize returns. Private family wealth offices have a long-time horizon for thinking about their investments because they are trying to build multigenerational wealth.”

In 2017, MIT Sloan started offering programs for high-net-worth families interested in impact investing. “My personal experience with family enterprise gave me a way to talk to these people and connect with them,” says Jay, noting that “in virtually every family business, the issues of succession and cross-generational priorities arise.” In 2018, Jay’s efforts gained momentum when John A. Davis, a globally recognized expert on family enterprise and wealth, joined the MIT Sloan faculty as a senior lecturer. “He took me under his wing,” says Jay, “and brought me into the community of people who were advising and researching family enterprise.” Together, they established a research initiative they called the Owning Impact Project.

Synthesizing MIT Sloan’s efforts

Under the umbrella of the Sustainability Initiative, Jay and Davis first conceived the Owning Impact Project “as a catchall for the work we do with families to enhance their social impact.” It became clear that among family business owners, there were three distinct categories:

1) Those still focused on their day-to-day operations and not yet in a position to think about impact investing on a large scale.

2) Families in what Jay calls a “middle zone” who have produced some liquid wealth and often have second-generation members seeking to use those resources to take on societal issues such as climate change and income inequality.

3) The newly wealthy such as tech and hedge fund entrepreneurs. These owners may have the greatest financial ability to do impact investing, says Jay, but are usually at the beginning of the learning curve.

A systems approach

“What’s been emerging,” says Jay, “is the whole question of ‘How do you invest for systems change?’ If we’re going to tackle the big issues—climate change, mental health crises, education challenges—they won’t be solved one entrepreneur at a time.” MIT Sloan is uniquely positioned to answer that question, he points out. “We are the systems place.”

As examples, Jay cites the influential work of John Sterman PhD ’82, the Jay W. Forrester Professor of Management and director of MIT’s System Dynamics Group, and of Andrew Lo, the Charles E. and Susan T. Harris Professor and director of the MIT Laboratory for Financial Engineering, which seeks to apply advances in financial engineering and computational finance for the betterment of society. “It’s natural that MIT Sloan would be an academic home base for this intersection.”

Deep dive into success stories

The Owning Impact Project’s graduate student researcher, Alban Yau SM ’24, analyzed 26 case studies of impact investors, building a taxonomy of approaches to investing for systemic change. He then homed in on one case study: the successful efforts of Jesse Fink, cofounder of the international travel site Priceline, and his wife, Betsy, who took a systemic approach to reducing food waste by investing not only in technological systems but also in human capital and orchestration of a network of fellow investors.

Yau and Jay’s case study on the Finks, published on the Social Science Research Network, says Jay, “is the first tangible, in-depth illustration of what systemic investing looks like.” The Finks began with small grants to nonprofit and seed fundings to early-stage ventures, built collectives to catalyze US national awareness of the food waste issue, and ultimately sparked billions of dollars invested by all types of funders of food waste solutions over the last decade.

Spreading the word

Jay wants more impact investors to recognize the benefits of a systems approach and sees MIT Sloan’s role as studying what works—and what doesn’t. “If we have a pipeline of people who are doing research on this topic, we’ll be fulfilling our purpose.” As Jay and his colleagues identify areas of potential change, they can help guide family business owners.

“There are capital allocation decisions that systemic investors make,” he says, “between investing in solutions and investing in the enabling conditions for those solutions. Leverage points might include everything from physical infrastructure to investing in advocacy that seeks to change public policy.”

Jay hopes that in the future, “we’ll take it beyond a family enterprise conversation to understand that systemic investing can be engaged in by government agencies and institutional asset owners. The starting point is looking at what these family owners are doing and seeing that their work can be catalytic.”