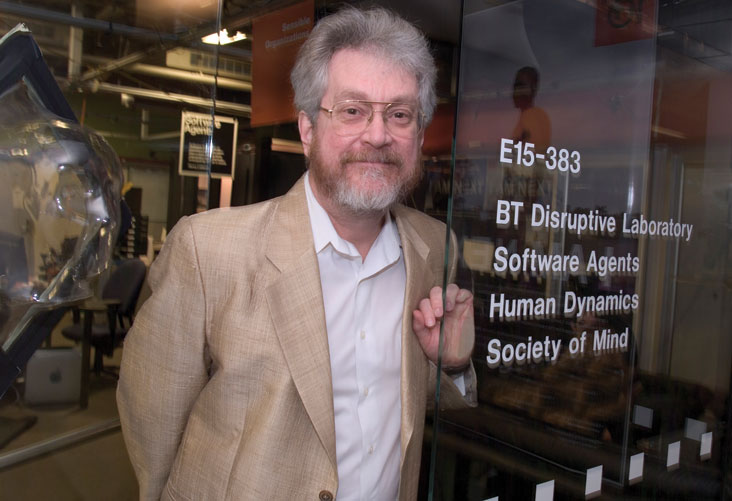

Prof. Sandy Pentland says that understanding honest signals will make us better managers, workers, and communicators.

PHOTO: ED QUINN

“There was too much charisma in the room,” he says. “These were world leaders and entrepreneurs who had created billion-dollar companies, and they would say something with conviction and passion, and you’d think, ‘Wow, that’s incredible, and we’d all vote, yes.’ A day later, you’d realize, that’s just stupid. There was something about the certainty of the person that shut off your conscious brain and made you believe it.”

Prof. Alex “Sandy” Pentland says that he can now tell when someone is bluffing, paying attention, or is genuinely interested, because beyond language, there is another communication network — unconscious social patterns that reveal our true attitudes. He calls them honest signals. He says that this communication network profoundly affects our decisions, and if we can learn to read the signals, we can predict with startling accuracy the outcomes of many situations, including salary negotiations, job interviews, and first dates.

Pentland, the Toshiba Professor of Media Arts and Sciences, leads the MIT Human Dynamics Lab, which develops human-focused technology. He co-directs the Digital Life Consortium, a group of 20 multinational corporations that explore new ways to innovate. And he was also co-founder of MIT’s Legatum Center for Development & Entrepreneurship, which supports aspiring entrepreneurs in emerging markets. In 1997, Newsweek named Pentland one of the 100 Americans likely to shape the century.

The author of Honest Signals: How They Shape Our World, published this fall by MIT Press, Pentland says that honest signals are biological and evolved from ancient primate signaling. He adds these examples:

- If someone begins to mirror your movements, you will probably begin to mirror theirs. When a pair mimics each other, they are more empathetic. (In a salary negotiation, for example, Pentland and his collaborators found that when one began mimicking the other — nodding their head or folding their hands — they also trusted each other more.)

- Just as kids bounce around when they’re genuinely happy, when you’re interested and excited, you unconsciously increase your activity level.

- When our thoughts and emotions are focused and consistent, our speech is more fluid. This signals that we know what we’re talking about, so listeners tend to believe we’re right.

- If your pattern of speaking influences that of other people, chances are good that you’ll get them to agree with you.

“You really can’t fake these signals,” Pentland says. “Moreover, your signaling affects your own attitude. If you try to act with enthusiasm, for example, you wind up actually becoming more enthusiastic.”

NOW WE CAN MEASURE

Pentland and his group developed a sociometer, a device that looks like an ID badge that automatically measures the signaling of individuals and groups. In multiple experiments at banks, hospitals, and sales centers, they asked employees to wear the badge for one month. It’s a way to X-ray the performance of an organization, and Pentland adds that these new tools could revolutionize management.

At a Chicago data systems firm, for example, where everyone wore the badge for a month, Pentland and his collaborators found that many people in the company lacked a cohesive set of face-to-face relationships. “If everybody around the water cooler talked to each other, then they were as much as 30 percent more productive. The workers in this organization seem to need this social support, but it was something that was not part of the management plan at all.

“What we found is that in many organizations, managers manage only what they can measure and forget the human element. Yet cohesive face-to-face relationships are an important part of the ability to integrate information and can allow teams to be more creative.

“You can’t manage what you can’t measure,” he says, adding that there’s been no way to measure human communication until now.

NEW TECHNOLOGY

This sensing technology, he believes, will create a predictive science in human organizations. At a medical institution, for example, his group was able to identify when there was going to be a problem with the patients or with a medical process, just by looking at the signaling between people.

Using this data to create a live, “quality-of-life” map, he says, we one day could tell where people are fully employed, or how well they are connected to the rest of society. We could better manage cities, buses, and construction projects, or even locate outbreaks of infectious disease.

While we could use the power for good, Pentland says, it could also feel like Big Brother is watching. That’s why he and his colleagues recently called together several companies and governments to create “a new deal on data,” to establish rules to protect the individual.

“These new tools can give people feedback. Many people have a poor social sense. By feeding back to them what they’re doing, they can learn to behave more appropriately,” Pentland says. “The point of Honest Signals is that if we pay attention to these ancient signals, we can do much better as a society.”