MIT student interns, Tulsa Advanced Science Camp instructors, and high school student participants gather at the University of Tulsa.

PHOTOS: COURTESY OF PKG

One undergraduate, Jack Carson ’28, reached out to the Priscilla King Gray (PKG) Center for Social Impact (formerly the PKG Center for Public Service) before his first year had even begun to pitch an ambitious idea. As a member of the Cherokee Nation who grew up in Oklahoma, he wanted to bring an advanced STEM camp to Tulsa, OK, for high school students enrolled in federally recognized Native American tribes.

Founded in 1988, the PKG Center has developed deep expertise in experiential social impact education for STEM students, and in helping students realize their personal vision of positive social impact. The center, which has helped many MIT students develop K-12 STEM camps in their home communities, has experience creating programming with Native American tribal communities.

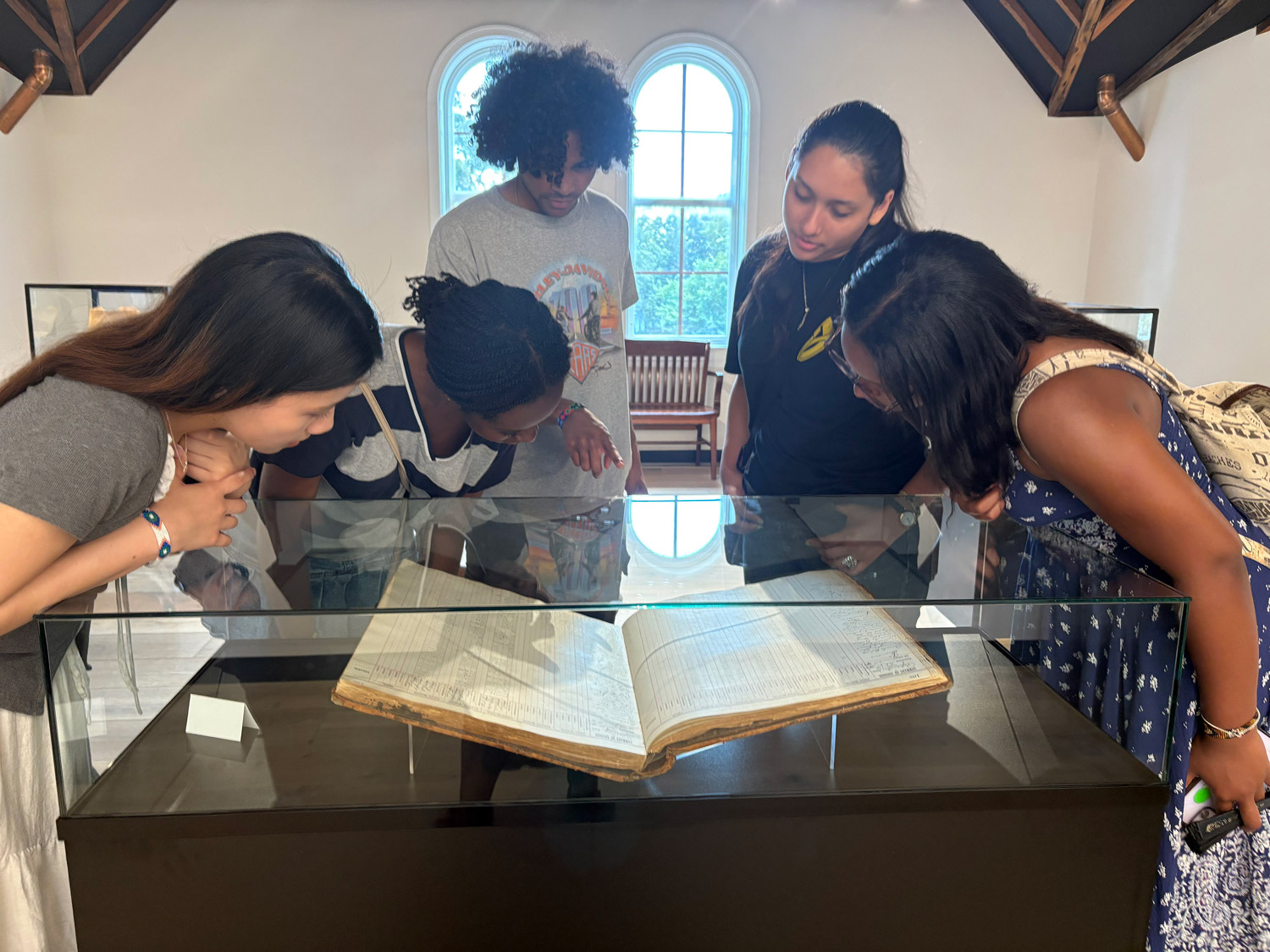

In September 2024, PKG Center staff traveled to Tulsa to meet with Native Nations and local nonprofits to explore opportunities to collaborate, then developed summer internship positions for nine undergraduates with the Cherokee Nation, the Muscogee Nation, and local nonprofits including Black Tech Street to execute AI, data science, and coding projects. During MIT’s Independent Activities Period in January 2025, Carson developed what became the Tulsa Advanced Sciences Camp (TASC) for tribal youth. The plan was for MIT interns to live in housing provided by the University of Tulsa (TU), and in the final week of summer, after completing their internships, they would help to run the STEM camp for high school students, also hosted by TU. The initiative, which Carson named Code.Tulsa: Igniting Tech Futures, would enable MIT undergraduates to both support and learn from the tech-based socioeconomic development strategies at work in the Tulsa region.

Building leadership skills

Growing up in Oklahoma, Carson was involved in Tribal Youth Council, an organization founded in 1989 to get young members of the Cherokee Nation involved in current events and train them to be leaders in modern society. Through that experience, “I made a lot of contacts and became very interested in the broader Native welfare across the United States,” he says.

Carson’s desire to bring high school students to TU for STEM and coding camp was a result of his own educational experience. “In the Cherokee Nation,” he says, “less than 5% of high schools offer a serious calculus class, and only two high schools offer a non-trivial computer science class.” Carson was fortunate to be able to enroll at TU concurrently with high school for two years, gaining access to more demanding curriculum.

“This is something that I’m very grateful for,” he says, pointing out that students living further from major universities might not have the same opportunity. “Doing outreach for the Tribal Youth Council, he says, “I found that people in rural communities wanted to be successful. They wanted to help their tribe, but they didn’t know which levers to pull in order to achieve that.”

From Cambridge to Tulsa

Year one of Code.Tulsa was supported by a grant from the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation. By all accounts, it was a smashing success. Nina Ruiz-Garcia ’27, who was inspired to join after seeing the PKG Center’s outreach, reflects, “It sounded like a really cool program that gave me a lot of hope. I hadn’t been exposed to the PKG Center yet and found that their mission and goals and values really aligned with mine. I was excited to apply.” Ruiz-Garcia and two other students worked in the IT department of the Cherokee Nation to digitize tribal registration.

“[The MIT students] brought to life a project that had been a dream for years, and almost in the same breath, they jumpstarted an entirely new initiative that would have taken us years to launch without them,” says Paula Starr, chief information officer of the Cherokee Nation. “Their creativity, drive, and fresh perspective made a lasting impact on our team and our mission.”

PKG Center assistant dean Vippy Yee also lived at TU for the summer to oversee the internship program, which was enhanced by weekly educational dinners featuring local leaders, including representatives from the Tulsa Mayor’s office and the Tulsa Innovation Labs. Yee also organized and led cultural outings for interns on the weekends.

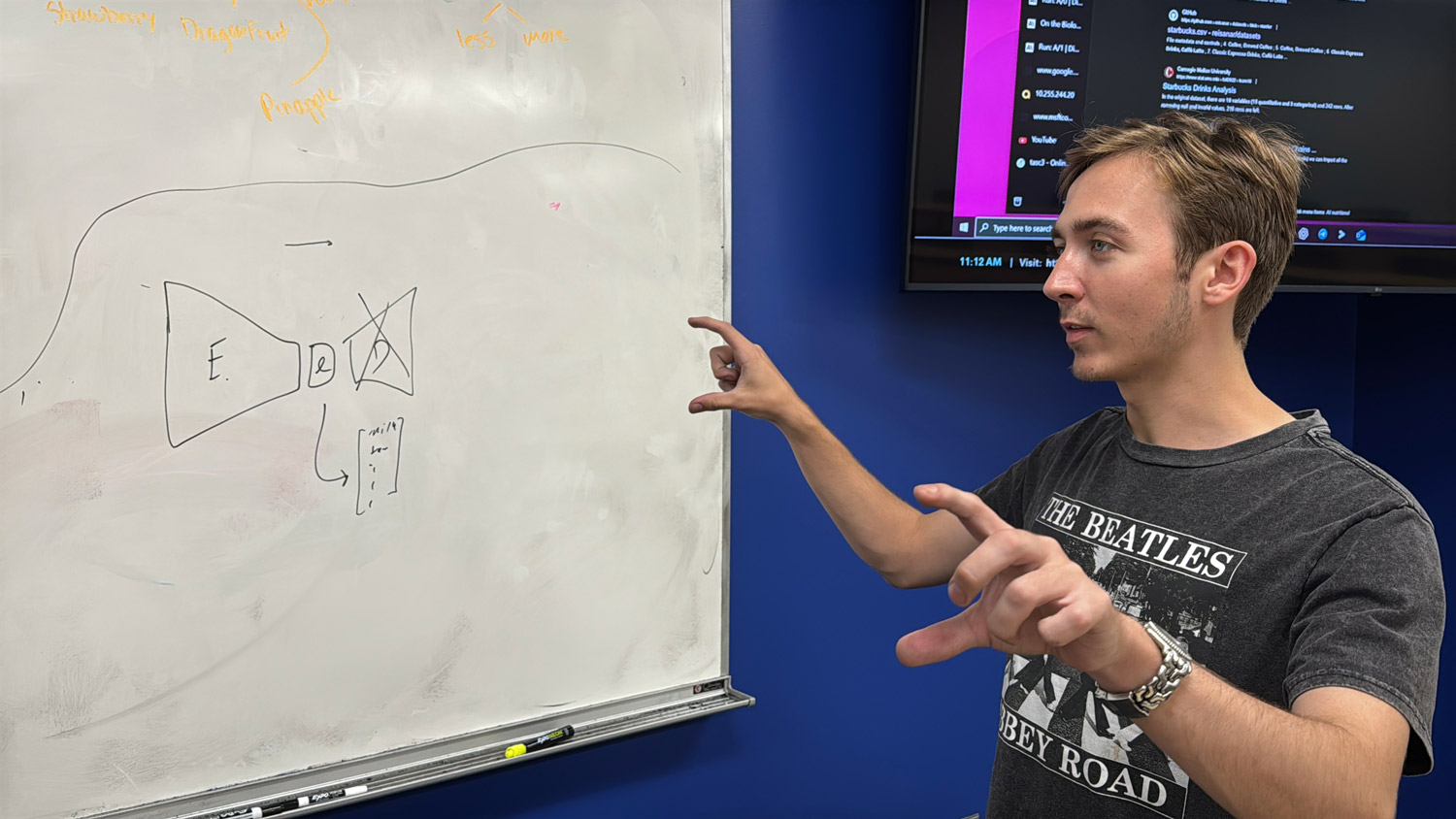

A week of rigor—and fun

During the final week in Oklahoma, MIT students conducted the STEM camp for high school students. The goal was “to give students the vision of what it takes to succeed and make a meaningful impact” on their communities, Carson said. There were three tracks: biology; physics, and AI. Four hours a day were spent in small groups of 4 or 5 students with one MIT mentor giving lectures. “These were very intense, conceptually rigorous, moving at a breakneck pace through a lot of really advanced topics.”

“In the afternoons we had a series of workshops,” he continues. “These were more about things like how to think, how to know, how to argue, how to identify which values are the most important to you.” Guest speakers ranged from a Catholic philosopher to a computational chemist, all invited to share their perspectives about a topic of their choice.

Feedback from the high school students at the end of the week was very positive. “Jack on day one said over and over, ‘Ask questions, even the dumbest questions,’” said one student. Many students commented that they enjoyed learning from undergraduates who were “passionate about the material and easier to understand because they were closer to us in age.” Students left TASC with a more ambitious vision for their future, with one commenting: “A lot of kids don’t know where they want to go and this is a really good place to find what your values are and where your interests lay.” Some spoke about taking more AP classes in the coming year, and others have been in touch with Carson since the camp concluded for advice on applying to college.

The MIT students also enjoyed the experience. “The high school students were very bright, motivated, and excited about exposure to a new world,” says Ruiz-Garcia, who noted that some participants began the week with limited knowledge of STEM, and left with a deeper appreciation for its relevance to their lives.

Outreach to remote areas

Carson believes that the most innovative aspect of the program was their method of recruiting talented high school students to apply. “I reached out to all of the contacts that I had made in three years of being involved in tribal politics, a variety of tribes, going straight to the heads of education and technology. So the education secretary for the Cherokees would send it out to the principals and the superintendents, who then send it out to the school counselors, who would send it to the teachers.” Ultimately, says Carson, more than 70% of the participants came from rural and highly underserved communities, “We’re really, really proud of that.”

He looks forward to working with the PKG Center to grow the program, anticipating a larger cohort of high school students for next year. Reflecting on his own journey to MIT, Carson says, “I wanted to be excellent, and to go somewhere where I thought the best would be. I knew that MIT is an institution that would hone one into the best, most intelligent, and most capable version of themselves.” In the future, he plans a career in research and science but intends to remain deeply connected to tribal welfare in Oklahoma. “It’s something that my family has been involved in for literally six generations.”

A model for the future

“Code.Tulsa serves as a model for the type of outcomes-oriented, thematic initiatives the PKG Center will pursue in the future,” says Alison Badgett, associate dean and the center’s director. The PKG Center recently completed a new strategic plan which prioritizes supporting student engagement in MIT’s social impact priorities, such as expanding access to K-12 STEM education, leveraging AI for the public good, and complementing an engineering education with a humanist lens on social interventions.

“Tulsa is an ideal place for students and others at MIT to turn theory into action, ethics into tactics, particularly in relation to leveraging AI for the public good,” says Badgett, pointing to internship partner Black Tech Street as an example. Black Tech Street recently announced a partnership with Nvidia to establish Tulsa as a national model and testing ground for AI education and innovation. MIT interns helped develop a white paper for Black Tech Street on socio-technical frameworks for AI integration, and this fall, PKG is placing additional students with the organization to research AI-driven workforce development. “The PKG Center sees Code.Tulsa as a long-term engagement in the Tulsa region.”

SUPPORT THE PRISCILLA KING GRAY CENTER

Your support for the PKG Center for Social Impact and programs like Code.Tulsa is invaluable. Make your gift.