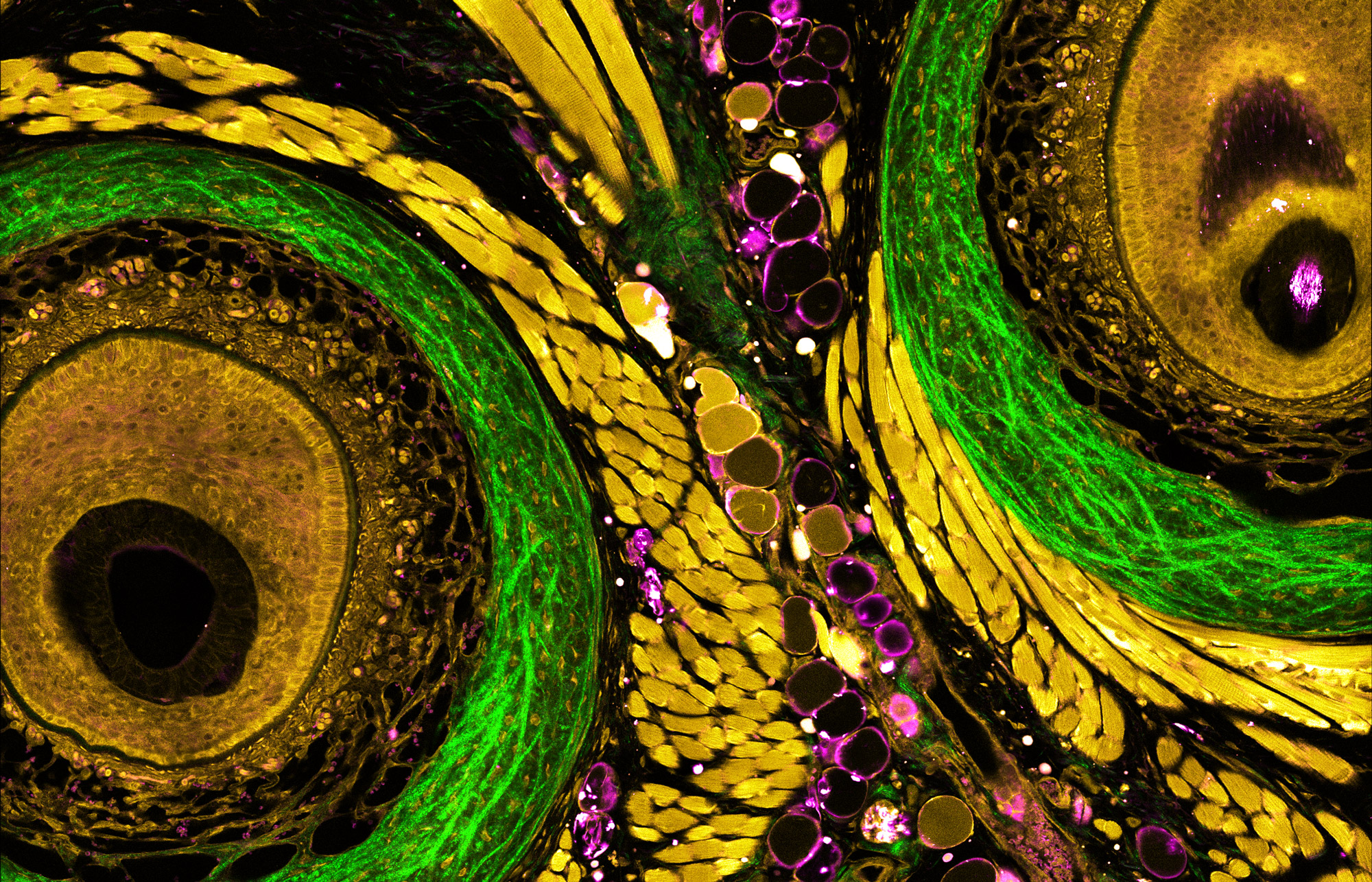

Part of a study on neuropathic pain, this image depicts the rich microenvironment of an unprocessed intact mouse whisker pad.

IMAGE: 2024 KOCH INSTITUTE

Title

7.27 Principles of Human Disease

Instructors

- David Housman, Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Professor for Cancer Research; Intramural Faculty, Koch Institute

- Yadira Soto-Feliciano, Howard S. and Linda B. Stern Career Development Professor; Intramural Faculty, Koch Institute

From the syllabus

In this course, you will explore contemporary approaches to human disease research, examining molecular and cellular mechanisms through both established and innovative techniques. Topics include the genetics of simple and complex traits, high-resolution karyotypic analysis, positional cloning, and modern diagnostics such as next-generation sequencing and CRISPR-based genomic editing. The curriculum addresses infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS, COVID-19 and emerging pathogens, as well as genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in cancer and other disorders. Additionally, you will investigate advanced disease models, from animal systems to computational models, and discuss precision medicine strategies for targeted therapies. Throughout the course, you will engage with primary research literature through critical discussion and will be required to develop a research proposal focused on a disease of your choice.

Class structure and assignments

Principles of Human Disease is divided into three modules that give time to three categories of disease/disorder: infections including viruses, bacteria, and parasites; diseases caused by genetic mutations, such as cancer or a disorder called phenylketonuria (PKU) that prevents the breakdown of certain amino acids; and diseases that affect multiple systems of the human body—for example, metabolic or cardiac issues. Within this last category, students hear about emerging diseases or “a combination of symptoms that before were ascribed to or misdiagnosed as other diseases or disorders,” says Soto-Feliciano.

The course meets twice weekly during the spring semester. The first session follows a more traditional lecture and note-taking structure, introducing the concepts of focus for that week. In the second session, students present on a relevant, peer-reviewed article in a journal club style.

“Their job is not to just have a monologue,” says Soto-Feliciano. “They must really engage with the rest of the class and ask questions.”

The students not in charge of running the paper’s discussion are expected to submit a short video of themselves explaining the key concepts of the research as though to a layperson. Not only does this encourage them to drill down into the paper, it prepares them for types of communication they’ll need to do in their careers.

“In the current environment, a short video presentation is often the way in which screening for grants, early-stage biotech funding, and academic positions are carried out,” says Housman.

Each year, the classroom welcomes back a series of guest speakers who have firsthand experiences with the diseases the students are studying. In one, a researcher discusses being a genetic carrier of myotonic dystrophy, a type of muscular dystrophy. In another, Alan Grossman, the Praecis Professor of Biology at MIT, talks about what led to him needing a heart transplant and its aftermath. In the clinic on PKU, students hear from a family who has been involved in this class for more than a decade.

“Our PKU family has become a fixture in 7.27,” says Housman. “The students learn from the family and their daughter with PKU how the blood-screening test that was carried out immediately after their daughter was born allowed the family to make the dietary/biochemical changes necessary to dramatically improve their daughter’s quality of life. Meeting and conversing with their now-adult daughter has had a profound impact for the students in 7.27.”

“Understanding how these conditions affect people’s lives contextualizes the research that you would do and also helps inform and direct it,” says computational and systems biology major Sophia Cai ’26, who took the class in spring 2025.

Engaging with knowledge

There are no tests in Principles of Human Disease. Students take away the bits of knowledge and scientific connections that most resonate with their specialties and research interests, which have included biology, chemistry, engineering, computer science, and business.

“Everybody’s expertise is different enough where in every in-class discussion, someone brings up a whole new perspective that they know a ton about because that’s their research focus. If someone had a gap in knowledge, there was always someone who knew what was going on,” says Alexis Boykin ’25, a spring 2025 student. Students explore those personal interests through the course’s semester-long writing assignment, inspired by the process of drafting and iterating on an NIH-style grant proposal.

“Writing research proposals as an undergrad is one thing,” says Cai, who proposed a study on prion disease. “But by doing your own research for a disease that you choose and then picking a project based on the most up-to-date literature, it’s prepping you for what you would actually do as a researcher.”

A unique approach

Disease will always be part of the human experience, an act brought home in stark terms by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It really highlighted how quickly a field can move when the pressing need is in front of us,” says Soto-Feliciano. That’s why she and Housman have modified the curriculum in the years since to include the weekly journal review. “Now the class has a slightly different flavor. Students are interfacing with well-established facts, but also with emerging concepts in the literature.”

Principles of Human Disease’s approach is unique among biology courses. Diseases are usually covered as part of a broader human biology education with a heavy emphasis on mechanisms, but not much discussion of research methodology or review of the state of the field.

“We’re trying to highlight spaces for students to get excited about that they potentially can go on to after they finish med school or grad school and maybe tackle some of those diseases,” says Soto-Feliciano.

Soto-Feliciano knows the course’s impact. She was a teaching assistant for Principles of Human Disease when she was a PhD student a decade ago. In the years since she returned to MIT and began teaching, she has gotten many requests from students for letters of recommendation or to review their graduate school application statements, all of which cite this class as a transformative experience.

Boykin agrees wholeheartedly. She graduated just after taking the class and is now working on diseases related to ribosome dysfunction in the MIT lab of Eliezer Calo, associate professor of biology. “This was hands-down one of my favorite classes of all at MIT,” says Boykin. “Every day I left knowing a lot more than I did entering.”